When the FDA approves a generic drug, you might think it’s just a matter of weeks before it hits pharmacy shelves. But in reality, many approved generics sit on shelves in warehouses-patent litigation keeps them locked away for years. Between 2023 and 2025, this wasn’t an exception. It was the norm.

Why Approved Doesn’t Mean Available

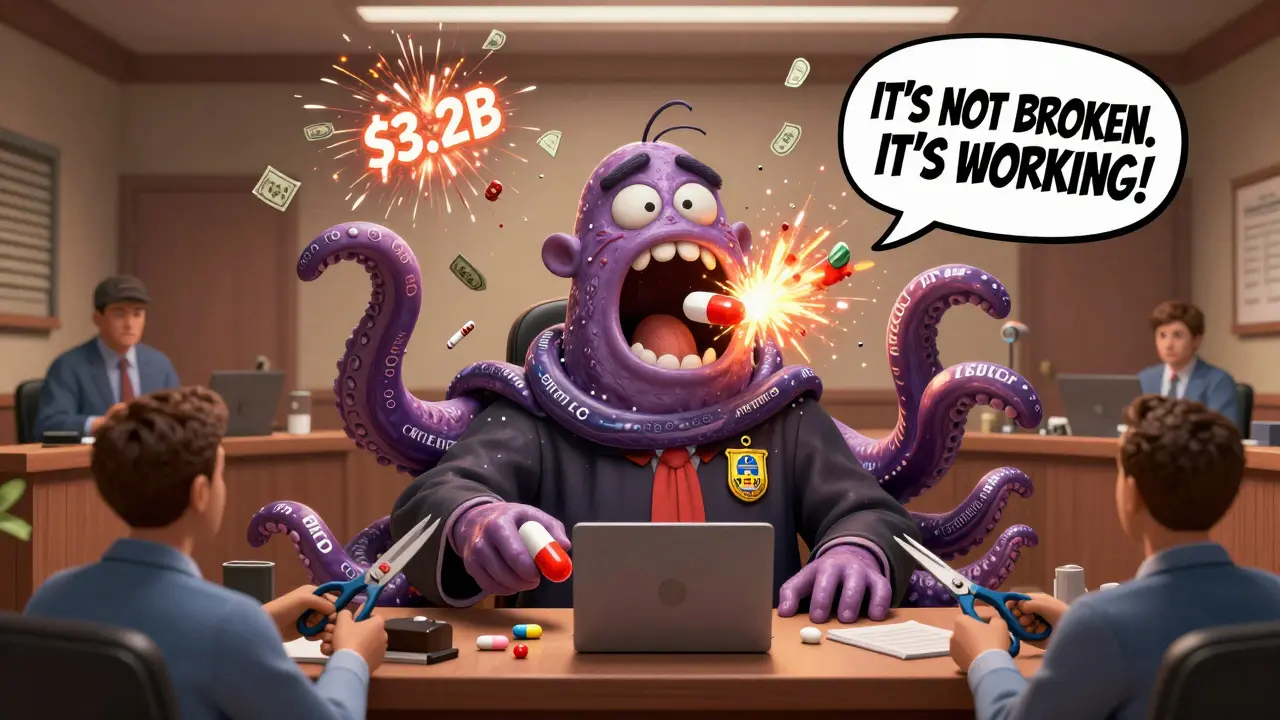

The FDA approved 63 first-time generic drugs in 2025 alone. But according to a 2024 study in the Journal of Generic Medicines, the average time between FDA approval and actual market launch stretched to 3.2 years. That’s not a glitch. It’s a system. The reason? The 30-month statutory stay. When a generic company files an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) and certifies that a brand-name drug’s patent is invalid or won’t be infringed (called a Paragraph IV certification), the brand company can sue. That lawsuit triggers an automatic 30-month delay in FDA approval, even if the patent is weak or already expired. In 2024, 68% of all generic applications included this kind of patent challenge. And the number of patents listed per drug? It jumped from 12.3 in 2020 to 14.7 in 2025.Patent Thicketing: The Real Game

Brand-name companies aren’t just defending one patent anymore. They’re building walls of them-dozens, sometimes hundreds. This is called patent thicketing. Take Humira. Its basic patent expired in 2016. But through 242 separate patent filings, AbbVie kept competitors out until 2023. That’s seven extra years of monopoly, all legal under current rules. Dr. Aaron Kesselheim from Harvard Medical School put it bluntly: “The current patent thicketing strategies have extended monopolies beyond the intended 20-year term by an average of 3.7 years per drug.” That’s not innovation. That’s delay tactics dressed up as legal rights.Who Gets Hurt?

Patients pay the price. A survey by Patients For Affordable Drugs Now found 412 cases between 2023 and 2025 where people couldn’t afford their meds because the generic they were promised never arrived. For drugs like Eliquis, Trulicity, and Xarelto, brand versions cost $487 a month on average. The generic? Around $85-if it ever launched. Pharmacists are fielding calls daily. One pharmacist on Drugs.com wrote in August 2025: “We had the generic for Xarelto approved last November but still can’t get it. The brand company filed three new patents last month. Now we’re looking at another 30-month delay.” Hospitals are suffering too. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists reported that 78% of hospital pharmacy directors see patent delays as a major contributor to drug shortages-especially for injectable oncology drugs. Between 2023 and 2025, 14 out of 15 oncology drug shortages were linked to injectables, and 37% of those delays were tied to active ingredient supply issues. But even those supply problems are often worsened by patent fights that freeze production.

Complex Generics Face Longer Delays

It’s not just pills. Complex generics-inhalers, injectables, eye drops-face even longer waits. Why? They’re harder to copy. But patent delays hit them harder too. Eighty-nine percent of delayed complex generics faced patent-related blocks, compared to 63% of simple oral tablets. Oncology drugs had the longest delays: 4.1 years on average between approval and launch. Cardiovascular generics? 2.8 years. Central nervous system drugs? 2.3 years. The pattern is clear: the more complex the drug, the more patents are thrown up to block it.Why the FDA Can’t Fix This

The FDA can approve a drug. But it can’t force a patent to expire. That’s the law. Dr. Patrizia Cavazzoni, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, admitted in May 2025 testimony: “Patent litigation remains outside our regulatory authority.” The agency has tried. It’s updated the Orange Book to make patent listings more transparent. It launched an AI-assisted review system in 2025 that cut review times by 22% for non-litigated applications. But when a lawsuit is filed, the 30-month clock starts-and nothing the FDA does can stop it. The new National Priority Voucher program promises to speed up reviews for certain drugs-from 10 months to just 1 or 2. But it doesn’t touch patent stays. So for the vast majority of generics caught in litigation, it’s irrelevant.The Financial Toll

The cost isn’t just emotional. It’s financial. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that patent delays cost Medicare Part D $3.2 billion a year in extra spending on brand-name drugs that should be generic. The top 10 drugs losing exclusivity in 2025 had $78.3 billion in annual sales. That’s billions in profits locked in by legal delays. Johnson & Johnson’s Stelara, Amgen’s Prolia, Regeneron’s Dupixent-all sitting on billions in revenue because generics couldn’t enter. Meanwhile, generic drug manufacturers are spending more than ever to fight these battles. Legal costs per case jumped from $9.3 million in 2023 to $12.7 million in 2025. Small and mid-sized generic companies-those with under $500 million in annual revenue-are hit hardest. Sixty-three percent of delayed generics involve these smaller players. Big pharma can absorb the cost. Smaller ones often can’t.

What’s Changing?

Some things are shifting. The practice of brand companies launching their own “authorized generics” to block competition has dropped sharply-from 28% in 2020 to just 12% in 2025. That’s progress. But it’s not enough. The FTC has stepped up. In 2024 and 2025, it filed seven enforcement actions against companies using patent strategies to delay competition. One case against Jazz Pharmaceuticals over Xyrem ended in February 2025 with a settlement forcing earlier generic entry. Congress has tried, too. The CREATES Act, designed to give generic makers easier access to the samples they need to test their drugs, passed the House in 2024 but stalled in the Senate in 2025. Without it, brand companies can still refuse to sell samples, effectively blocking generic development. And then there’s the Hatch-Waxman Act itself-the 1984 law that created the modern generic approval system. It’s outdated. Sixty-seven percent of industry stakeholders surveyed by McKinsey in 2025 support limiting the number of patents that can be listed per drug. But PhRMA, the big pharma lobby, fights every change, saying it would hurt innovation.What Can Be Done?

The path forward isn’t simple, but it’s clear:- Cap the number of patents that can be listed per drug. Right now, there’s no limit. That’s a loophole.

- Shorten the 30-month stay. If a patent is clearly invalid, why wait two and a half years?

- Require brand companies to disclose all patent claims upfront. No sneaky additions after the fact.

- Give the FDA more power to review patent listings for abuse-like evergreening tactics that just tweak a drug’s coating or dosage.

The Bottom Line

The system isn’t broken. It’s working exactly as designed-for brand-name companies. But it’s failing patients, pharmacists, hospitals, and small generic makers. The FDA can approve a drug in 14 months. But if a patent lawsuit is filed, that approval sits idle for years. The question isn’t whether generics are safe or effective. They are. The question is: why does the law let a single company hold a drug hostage for years after its patent should have expired? And who’s going to fix it?Why do generic drugs get approved but not launch?

Generic drugs often get FDA approval but can’t launch because brand-name companies file lawsuits over patents, triggering a 30-month legal stay. Even if the patent is weak or expired, the FDA can’t give final approval until the court case ends or the stay expires. This is part of the Hatch-Waxman Act and happens in over 60% of generic applications.

How long do patent delays typically last?

The average delay between FDA approval and market launch for generics is 3.2 years (2024 data). For complex drugs like injectables or oncology treatments, delays can stretch to 4.1 years. This is mostly due to patent litigation, not manufacturing or supply issues, which account for only 37% of delays.

What’s the difference between a generic and an authorized generic?

A generic is made by a different company after the brand patent expires. An authorized generic is made by the brand company itself and sold under a different label. Brand companies used to launch authorized generics to block competitors, but this tactic has dropped from 28% of cases in 2020 to just 12% in 2025, suggesting a shift in strategy.

Why are oncology drugs delayed the most?

Oncology drugs have the longest delays-4.1 years on average-because they’re often complex injectables, which are harder to copy. Brand companies also file more patents on these drugs, and the financial stakes are higher. A single oncology drug can generate billions in annual sales, so companies fight harder to keep generics out.

Is the FDA trying to fix this?

The FDA has improved transparency in the Orange Book and launched AI tools to speed up reviews-but it can’t override patent lawsuits. Patent disputes are handled by courts, not the FDA. The agency has called for reforms to prevent patent thicketing, but it lacks legal authority to stop delays caused by litigation.

What’s the impact on Medicare patients?

Patent delays cost Medicare Part D an estimated $3.2 billion annually in 2025. Patients pay $487 per month for brand-name drugs when generics-approved and safe-could cost $85. Many skip doses or stop treatment because they can’t afford the brand version.

Are biosimilars facing the same delays?

Yes. Biosimilars face even more complex patent landscapes. For example, Humira had 242 patents listed, delaying biosimilar entry for over a decade. The average number of patents challenged per biosimilar application rose from 5.2 in 2020 to 9.7 in 2025. While 17 biosimilars were approved by Q3 2025, many still face multi-year litigation delays before launch.

What’s the difference between the U.S. and Europe on generic delays?

Europe has faster generic entry-1.7 years between approval and launch, compared to 3.2 years in the U.S. That’s because European countries don’t have the same patent linkage system. Lawsuits don’t automatically block approval. Patents are handled separately, so generics can enter the market sooner unless a court rules against them.

So let me get this straight-big pharma can file 200+ patents on one drug just to keep prices sky-high? And we call this innovation? 🤦♂️ The FDA approves generics, but courts let corporations hold patients hostage? This isn't capitalism. It's feudalism with lawyers.

The structural flaws in the Hatch-Waxman Act are not merely procedural-they are systemic. The 30-month stay, originally intended as a reasonable buffer, has been weaponized into a de facto extension of monopoly rights. This constitutes a clear violation of the public interest principle underpinning patent law.

I just lost my mom to cancer last year... and she couldn't afford her meds because the generic was stuck in legal limbo for 4 years. I don't care about patents or lawsuits-I care that my mother cried because she had to choose between her treatment and paying the rent. How is this acceptable? Why are we letting corporations profit off dying people? 😭

It’s wild how we celebrate innovation in tech but punish it in pharma. You can’t patent a smartphone app for 20 years and then sue everyone who tries to make a similar one-but you can patent the color of a pill coating and call it ‘novel.’ 🤯 We’ve turned medicine into a monopoly game. And the players? They’re not even playing fair.

The data is clear: 78% of hospital pharmacy directors attribute drug shortages to patent delays. This isn't anecdotal. It's institutional failure. The FDA’s AI tools are a Band-Aid on a severed artery.

You guys are missing the point. The real issue isn't patents-it's the lack of API diversification. Teva and Sandoz are already on it, using 3.4 suppliers on average. If you're still relying on one source, you're the problem, not the system.

I know it feels hopeless, but change is coming. The FTC is finally cracking down-Jazz Pharma got nailed in February. And the drop in authorized generics? That’s a win. It’s slow, but we’re moving. Keep pushing your reps. This isn’t over.

America’s innovation ecosystem is being dismantled by regulatory capture. When you incentivize litigation over R&D, you don’t get cheaper drugs-you get a broken system. The EU doesn’t have patent linkage because they prioritize access over corporate rent-seeking. We need to wake up.

I work in a rural pharmacy. People cry when they find out the generic isn’t available. They skip doses. They ration. I’ve seen people split pills in half just to make it last. This isn’t policy. This is cruelty. We can fix this. We just have to want to.

The 30-month stay must be capped at 12 months for weak patents. No exceptions.

Patent thicketing = economic rent extraction disguised as IP protection. The Orange Book is a joke. The FDA needs authority to de-list frivolous patents. End of story. 🚫💊