Before 1983, fewer than 10 treatments existed for rare diseases in the U.S. Today, over 1,000 are approved. The shift didn’t happen by accident. It was built on one powerful idea: if companies can’t make money developing drugs for tiny patient groups, they won’t try. So Congress gave them a guarantee - seven years of exclusive rights to sell a drug for a specific rare condition. That’s orphan drug exclusivity.

What Exactly Is Orphan Drug Exclusivity?

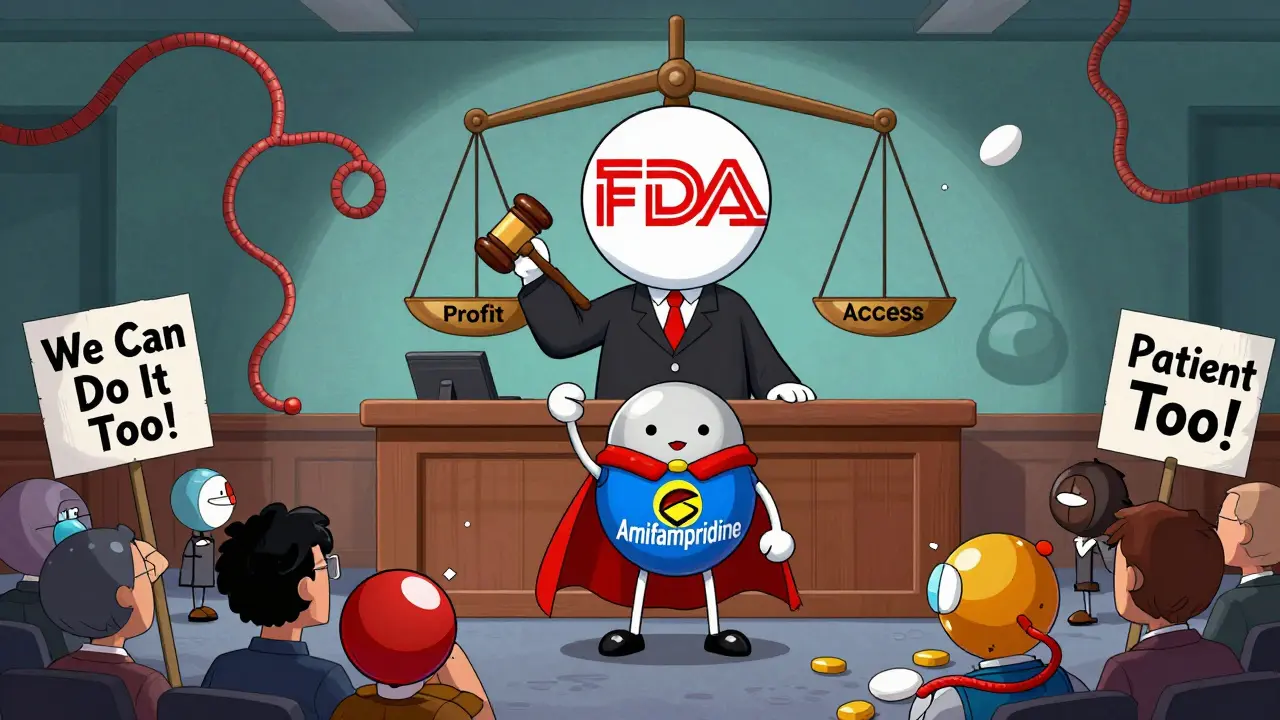

Orphan drug exclusivity is a legal shield granted by the FDA. If a company gets approval for a drug to treat a disease affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S., it gets seven years of market protection. During that time, the FDA can’t approve another company’s version of the same drug for the same disease - unless that new version proves it’s clinically superior. It’s not a patent. It’s not a trademark. It’s something else entirely. Patents protect chemical structures or methods of use. Orphan exclusivity protects a drug’s use for a specific rare disease. Two companies can have the same drug, but if one gets approved first for a rare condition, the other can’t enter that market for seven years - even if they developed it independently. This rule was created by the Orphan Drug Act of 1983. Before that, pharmaceutical companies had little reason to invest in rare diseases. The cost to develop a drug? Often $100 million or more. The number of patients? Sometimes just a few thousand. The return? Almost nothing. The Act flipped that math. Suddenly, even a drug for 5,000 people could be profitable - if no one else could copy it for seven years.How It Works: The Horse Race for Approval

Here’s the catch: multiple companies can apply for orphan designation for the same drug and same disease. But only one wins. It’s like a race where everyone lines up at the starting line with the same goal - get FDA approval first. The first company to get marketing approval gets the seven-year clock. The others? They can keep trying, but they can’t sell their version for that specific use until the exclusivity expires - or unless they prove their drug is better. What counts as “better”? The FDA requires a “substantial therapeutic improvement.” That means: better survival rates, fewer side effects, easier dosing, or something that clearly improves patient outcomes. In the 40 years since the law passed, only three cases have met this bar. This system creates urgency. Companies rush to finish trials, file applications, and get approval. Delays cost them the exclusivity window. Many start the orphan designation process during Phase 1 or Phase 2 clinical trials - years before they even think about selling the drug. The FDA reviews orphan designation requests in about 90 days, and approves 95% of them if the disease truly affects fewer than 200,000 people.What It Doesn’t Protect

Orphan exclusivity is narrow. It only covers the specific disease for which the drug was designated. If a drug is approved for two conditions - one rare, one common - the exclusivity only applies to the rare one. Take amifampridine. It was originally used for a common nerve disorder. Later, a company got orphan approval for it to treat Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS), a rare condition. Once approved for LEMS, the drug got seven years of exclusivity for that use. But doctors could still prescribe it off-label for other conditions, and other companies could still make generic versions for those non-orphan uses. This leads to what some call “salami slicing” - companies seeking multiple orphan designations for the same drug across different rare diseases. One drug might get orphan status for five different conditions. Each gets its own seven-year clock. That’s legal. But it’s also controversial. Critics argue some companies exploit the system by targeting diseases that aren’t truly neglected, just small.

How It Compares to Other Countries

The U.S. gives seven years. The European Union gives ten. And in Europe, companies can get an extra two years if they complete pediatric studies for the rare disease. The EU also has a loophole: if a drug becomes wildly profitable - meaning it’s used by more than 200,000 people - the exclusivity can be reduced from ten to six years. The U.S. doesn’t have that rule. That’s one reason some companies focus on U.S. approval first. Seven years is still powerful. And the FDA’s process is faster and more predictable than many others. In 2022, the FDA approved 434 orphan designations - up from just 127 in 2010. That’s a 240% increase in just 12 years.Why It Works - And Why Some Say It Doesn’t

The numbers speak for themselves. Before 1983, only 38 orphan drugs were developed in the U.S. Since then? Over 1,000. That’s not just progress. It’s a revolution in medical access. The system works because it removes the biggest barrier: financial risk. A biotech startup developing a drug for a disease affecting 8,000 people might spend $150 million. Without exclusivity, they’d go bankrupt. With it, they can charge a premium, recoup costs, and maybe even turn a profit. Patient advocacy groups know this. A 2022 survey by the National Organization for Rare Disorders found 78% of rare disease families say orphan exclusivity is “essential” for new treatments to exist. But there’s a flip side. Some drugs that got orphan status were already profitable. Humira, for example, received multiple orphan designations even though it treats common autoimmune conditions too. Critics say the system is being gamed - companies attaching orphan status to drugs that don’t need it, just to lock out competition and keep prices high. The FDA has noticed. In May 2023, they issued new draft guidance to clarify what counts as the “same drug” and when clinical superiority is truly required. They’re trying to close loopholes without killing the incentive.

What’s Next for Orphan Drugs?

The market is exploding. In 2022, orphan drugs made up $217 billion in global sales - nearly a quarter of all prescription drug revenue. By 2026, that number is expected to hit 21.1% of all global drug sales. Oncology leads the pack - over 40% of orphan drugs target cancer. But neurology, blood disorders, and metabolic diseases are growing fast. By 2027, Deloitte predicts 72% of all new FDA-approved drugs will have orphan designation. That’s up from 51% in 2018. The incentives are working - too well, some say. But for families living with rare diseases, the trade-off is clear: a drug that didn’t exist before is now available. Even if it costs $500,000 a year. The real question isn’t whether the system works. It’s whether we can make it fairer. Can we keep the incentive for true unmet needs while stopping abuse? Can we ensure that exclusivity leads to access, not just profit? Right now, the answer is still yes - but the pressure to reform is growing. The FDA, Congress, and patient groups are all watching. And for the families waiting for a treatment that doesn’t yet exist, the clock is ticking.How Companies Use This System

For small biotech firms, orphan exclusivity isn’t just helpful - it’s survival. Without it, they can’t attract investors. Venture capital doesn’t fund projects with no path to return. But with seven years of protected sales? Suddenly, a $150 million investment looks reasonable. Big pharma uses it differently. They buy small companies that have orphan drugs in late-stage trials. They get the approval, the exclusivity, and the pricing power - all without doing the hard work of early development. That’s why the top 10 orphan drugs brought in $95 billion in 2022. Humira, with its multiple orphan designations, made $21.2 billion that year - even though most of its use isn’t rare. The strategy? File for orphan status early. Build clinical data fast. Get approval before competitors. And don’t let anyone else get close.What Patients and Advocates Think

Rare disease patients don’t care about the legal mechanics. They care if a drug exists. And for the first time in history, they have more options than ever. Parents of children with spinal muscular atrophy, once a death sentence, now have multiple treatments. People with certain rare cancers live years longer than they did a decade ago. But the cost is a constant pain. A 2022 NORD survey found 42% of patient groups worry about drug pricing. Orphan drugs often cost hundreds of thousands of dollars per year. Insurance fights them. Patients go bankrupt. The exclusivity system makes the drugs possible - but doesn’t guarantee they’re affordable. Advocates are split. Some say: “Don’t touch exclusivity. Take it away, and the drugs vanish.” Others say: “Yes, we need incentives - but we also need price controls.” The truth? The system works for development. It doesn’t work for access. That’s the next battle.How long does orphan drug exclusivity last in the U.S.?

In the United States, orphan drug exclusivity lasts seven years from the date the FDA approves the drug for marketing for the rare disease. This period starts on the approval date of the New Drug Application (NDA) or Biologics License Application (BLA), not from the date of orphan designation or clinical trial start.

Can a generic drug be approved during the exclusivity period?

No - not for the same drug and the same rare disease. The FDA cannot approve a generic or competing version for that specific use during the seven-year exclusivity window. The only exception is if the competitor proves their drug offers a “substantial therapeutic improvement,” which has happened only three times since 1983.

Does orphan exclusivity replace patents?

No. Orphan exclusivity is separate from patent protection. Patents protect the chemical structure or how the drug is made or used. Orphan exclusivity protects the drug’s use for a specific rare disease. Most drugs have both. In fact, 88% of orphan drugs rely more on patents than orphan exclusivity to block competition. But orphan exclusivity can extend protection beyond what a patent covers.

Can one drug have multiple orphan designations?

Yes. A single drug can receive orphan designation for multiple rare diseases. Each designation comes with its own seven-year exclusivity period - if approved for each use. For example, a drug approved for three rare conditions could have up to 21 years of total exclusivity across those indications, assuming each approval is granted separately.

Why do some companies get orphan status for drugs that are already widely used?

The law only requires that the drug treats a condition affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. - not that the drug is new or that the disease was previously untreated. Some companies have used this to gain exclusivity for drugs already on the market for other conditions. For example, Humira received orphan status for rare forms of arthritis, even though it’s mainly used for common autoimmune diseases. This practice is legal but controversial, and the FDA is now tightening guidance around it.

Is orphan drug exclusivity the only reason new rare-disease drugs are developed?

No. Orphan exclusivity is one of three key incentives. The other two are tax credits (which cover 25% of clinical trial costs) and FDA user fee waivers (worth about $3.1 million per application). Many companies say the tax credits and fee waivers are more valuable than exclusivity. But without the seven-year market protection, few would risk the upfront investment - so it remains the most critical piece of the puzzle.

So we reward companies for making drugs for 5k people but let them charge $500k a year? Sounds like capitalism with a side of guilt trips.

At least the drugs exist.

lol at pharma buying small biotechs just to lock in exclusivity. it's not innovation it's financial jiu-jitsu.

also why does humira get 3 orphan tags? it's basically a miracle drug for EVERYTHING.

i think this system is actually genius but also kinda messed up. in india we dont even have access to 1% of these drugs and yet here in usa people are crying about pricing. i mean yeah its unfair but without this law we'd have zero options for rare diseases. my cousin has spinal muscular atrophy and she's alive because of nusinersen. so i dont wanna kill the goose that lays golden eggs even if the eggs cost 700k.

but yeah maybe cap the price or make them share with low income countries? idk just saying.

OH MY GOD I CAN’T BELIEVE YOU’RE NOT ANGRY ABOUT THIS 😭

THEY’RE JUST GIVING PHARMA A FREE PASS TO MONOPOLIZE AND ROB PATIENTS. I’M SICK OF THIS. 💸💀