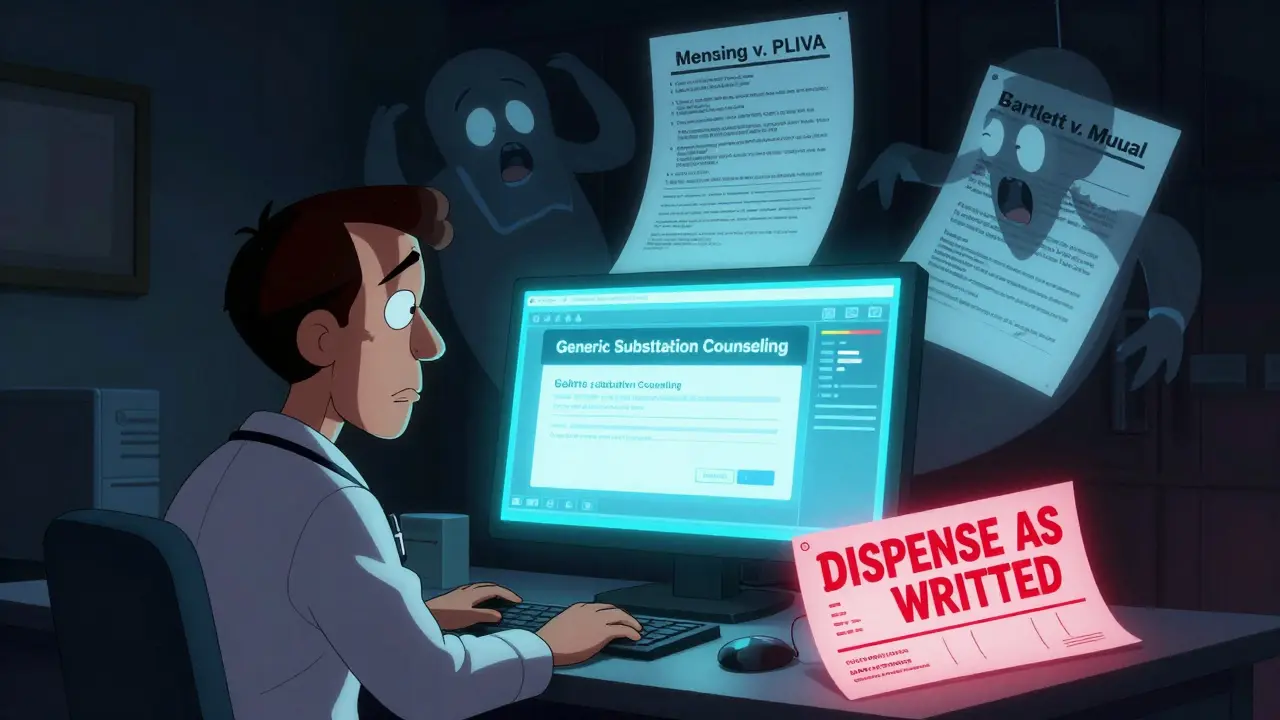

When a doctor writes a prescription for a generic medication, they’re not just choosing a cheaper option-they’re stepping into a legal gray zone that’s changed dramatically over the last decade. In 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in PLIVA v. Mensing a landmark case where the Court held that generic drug manufacturers cannot be sued for failing to update warning labels because federal law prohibits them from changing those labels without FDA approval. This decision, followed by Mutual Pharmaceutical v. Bartlett in 2013, which barred design defect claims against generic makers, created what legal experts now call the Mensing/Bartlett Preemption. The result? Patients injured by generic drugs have almost no legal recourse against the companies that made them. And that’s where physicians come in.

Why Doctors Are Now the Target

Before 2011, if a patient had a bad reaction to a generic drug, they could sue the manufacturer. Today, they can’t. Generic drugmakers are shielded from liability because federal law says they must copy the brand-name drug’s label exactly. They can’t add new warnings, even if new safety data emerges. So when something goes wrong-like a patient developing toxic epidermal necrolysis after taking generic sulindac, as in the Bartlett case-the injured person looks elsewhere. And the most accessible target? The doctor who wrote the prescription.

It’s not theoretical. Between 2014 and 2019, lawsuits against physicians involving generic drug injuries rose by 37%, according to the American Bar Association. A 2022 survey of 1,200 U.S. physicians found that 68% felt more anxious about prescribing generics. Nearly half admitted they sometimes prescribe the more expensive brand-name drug just to avoid potential lawsuits-even if it means higher out-of-pocket costs for their patients.

What Makes a Doctor Legally Responsible?

Medical malpractice claims, whether about brand or generic drugs, follow the same basic rule: duty, dereliction, direct cause. You have a duty to your patient. You must meet the standard of care. And if your action-or inaction-directly leads to harm, you can be held liable.

Here’s the catch: prescribing a generic drug isn’t automatically negligence. But failing to do certain things can be. For example:

- Prescribing a drug with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin or levothyroxine-without clearly stating "dispense as written" on the prescription.

- Failing to warn a patient about known side effects, such as drowsiness, dizziness, or skin reactions, especially if those effects could lead to serious harm (like driving or operating machinery).

- Not documenting that you discussed potential risks with the patient.

The Coombes v. Florio case set a precedent: a doctor was found liable after a patient, prescribed a sedative without warning against driving, caused a fatal crash. The same logic applies today. If a patient takes a generic anticonvulsant, develops Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and the manufacturer can’t be sued, the doctor’s failure to explain the risk becomes the focus of the lawsuit.

State Laws Vary-And So Does Your Risk

Not all states treat generic substitution the same way. Forty-nine states allow pharmacists to substitute generics unless the doctor writes "do not substitute" or "dispense as written." But what happens after substitution? That’s where things get messy.

Thirty-two states require pharmacists to notify the prescribing physician within 72 hours if a substitution occurs. Seventeen states have no notification requirement at all. That means a doctor might have no idea what medication their patient actually received. If the patient has a reaction, the doctor might be blamed for not knowing-despite having no control over the change.

And then there’s the legal patchwork. In 2014, Alabama’s Supreme Court briefly allowed patients to sue brand-name manufacturers for injuries caused by generics, under the theory that the brand maker should be responsible for the original label. But in 2015, the state legislature passed SB80, shutting that door. Meanwhile, in Illinois, courts have taken a different stance. In Guvenoz v. Target Corp. (2016), the state appellate court ruled that generic manufacturers do have a duty to update their labels-even if the FDA hasn’t approved it-when a drug is inherently dangerous. That means doctors in Illinois may face less liability than those in states that strictly follow federal preemption.

What You Should Be Documenting

Documentation isn’t just good practice-it’s your legal armor. The American Medical Association recommends specific language for every prescription involving a drug with known risks:

"I have discussed potential side effects of [medication], including [specific side effects], and advised you to avoid [specific activities] while taking this medication. You were informed that a generic version may be dispensed, and that side effects may vary slightly between brands and generics. You acknowledged understanding these risks."

Electronic health record systems like Epic have adapted. Since 2021, they’ve required physicians to complete mandatory "generic substitution counseling" fields before finalizing prescriptions. Skipping this step isn’t just sloppy-it’s risky. A 2023 report from Medical Risk Management, Inc. found that doctors who document detailed counseling reduce their liability exposure by 58% compared to those who just write "medication discussed."

And it’s not just about the prescription. If a patient has a history of adverse reactions, or if the drug is used for a life-threatening condition, you need to write "dispense as written" on the script. This is critical for drugs like:

- Warfarin (blood thinner)

- Levothyroxine (thyroid hormone)

- Phenytoin, carbamazepine (anti-seizure meds)

- Prograf, cyclosporine (immunosuppressants)

These drugs have narrow therapeutic windows. Even small differences in bioavailability between brand and generic can lead to overdose or underdosing-with deadly results.

Insurance, Costs, and the Hidden Price of Prescribing Generics

Your malpractice insurance premiums are rising-not because you’re making more mistakes, but because the legal landscape has shifted. According to the American Professional Agency’s 2022 analysis, physicians who routinely authorize generic substitutions without detailed counseling face an average 7.3% premium surcharge. That’s real money. For a primary care doctor earning $200,000 a year, that’s an extra $1,500 annually just for prescribing the cheaper option.

And it’s not just about lawsuits. A 2021 forum by the American College of Physicians documented 47 malpractice claims tied to generic drugs. Twelve of them resulted in settlements averaging $327,500. That’s not just financial-it’s emotional. One physician in Massachusetts told a Sermo forum: "I now add 15 to 20 minutes to every visit just to document warnings. I’m not getting paid for it. But I’m not risking my license either."

The Bigger Picture: Why This Isn’t Going Away

Generics make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. That’s not going to change. But the legal system is still catching up. The Supreme Court declined to hear Colvin v. United States in 2022, which would have challenged the Mensing/Bartlett doctrine. So the status quo holds.

But there are signs of change. In March 2023, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in Johnson v. Teva Pharmaceuticals that generic manufacturers can be held liable if they fail to update their labels after the brand-name maker adds new safety information. It’s a narrow exception, but it’s a crack in the wall.

Meanwhile, the American Medical Association is pushing model legislation to require pharmacists to notify physicians within 24 hours of substituting high-risk generics. Eighteen states have introduced versions of this bill in 2023 alone.

Legal scholars predict a 45% increase in physician-targeted lawsuits involving generics by 2027 if nothing changes. The pressure isn’t coming from patients-it’s coming from a legal system that’s left doctors as the only accountable party in a broken chain.

What You Can Do Today

You can’t control what the pharmacist dispenses. But you can control your documentation, your communication, and your awareness. Here’s a simple checklist:

- Always write "dispense as written" for narrow therapeutic index drugs.

- Document specific side effects and patient counseling in your EHR-don’t use generic phrases.

- Know your state’s substitution and notification laws.

- When in doubt, prescribe the brand-name version if the patient can afford it-and document why.

- Stay updated: new safety data on brand-name drugs may require you to update your counseling, even if the generic label hasn’t changed.

Prescribing generics is smart, cost-effective medicine. But in today’s legal climate, it’s no longer just a clinical decision. It’s a legal one. And if you’re not treating it that way, you’re putting yourself-and your practice-at risk.

Can I be sued if a patient has a bad reaction to a generic drug I prescribed?

Yes. Because federal law shields generic drug manufacturers from liability for failure-to-warn claims, injured patients are increasingly filing lawsuits against prescribing physicians. If you failed to document proper counseling, didn’t use "dispense as written" for high-risk drugs, or ignored known side effects, you could be held liable under medical malpractice standards.

Do I need to write "dispense as written" on every generic prescription?

No-but you should for drugs with narrow therapeutic indices, such as warfarin, levothyroxine, phenytoin, and immunosuppressants. These drugs require precise dosing, and even small differences in generic formulations can lead to overdose or treatment failure. In 32 states, writing "dispense as written" legally prevents substitution.

Is it legal to prescribe a brand-name drug just to avoid liability?

Yes. While it may seem unethical to choose a more expensive drug for financial reasons, courts have recognized that physician decisions made to reduce legal risk can be medically reasonable, especially for high-risk medications. The key is documenting your rationale clearly in the patient’s record.

What should I say to patients about generic substitution?

You should explain: (1) that a generic version may be dispensed, (2) that side effects may vary slightly between brand and generic, (3) what specific side effects to watch for, and (4) what activities to avoid (e.g., driving, operating machinery). Use clear, documented language-don’t rely on verbal warnings alone. Many malpractice cases hinge on lack of documentation.

Are electronic health records helping reduce liability?

Yes. Systems like Epic now require physicians to complete mandatory counseling fields before finalizing prescriptions for drugs with known risks. This creates a clear audit trail. Physicians who use these tools and document thoroughly have been shown to reduce their liability exposure by up to 58%.