At first glance, it seems backwards: Americans pay more for brand-name drugs than anyone else in the world, yet they pay less for the exact same generic versions. If you’ve ever filled a prescription for lisinopril or metformin at Walmart and paid $4, then traveled to Germany and seen the same pill priced at €15, you’ve seen the real-world impact of two wildly different systems. This isn’t a fluke. It’s the result of how each side of the Atlantic structures its drug market-and who’s really paying for innovation.

How the US Keeps Generic Prices Low

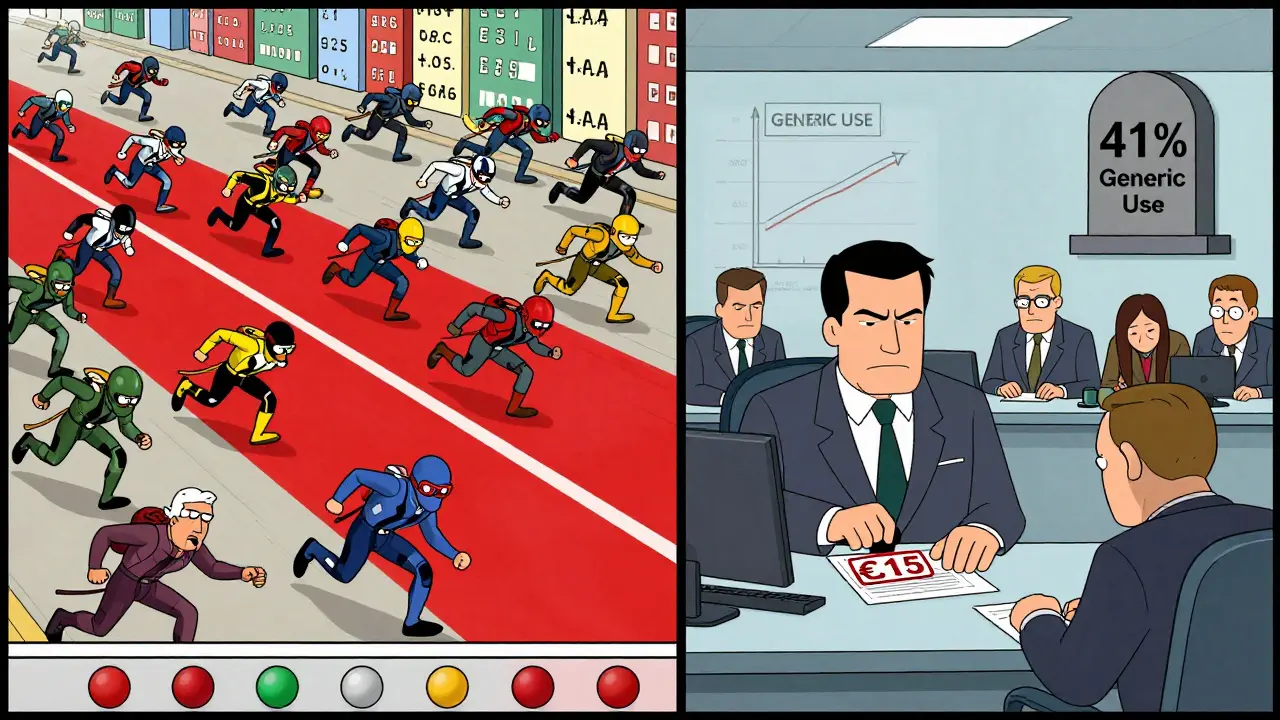

The United States doesn’t set drug prices. Instead, it lets competition do the work. Once a brand-name drug’s patent expires, dozens of companies can start making the generic version. Companies like Teva, Mylan, and Sandoz fight for market share by undercutting each other’s prices. This isn’t just theory-it’s happening right now. In 2023, 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. were for generics. That’s not a coincidence. It’s the result of a system designed to drive prices down through volume and competition. Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) play a huge role. These middlemen negotiate rebates with drugmakers on behalf of insurers. For brand-name drugs, those rebates can be 35-40% off list prices. But for generics? There’s no rebate system. The price you see at the pharmacy is often the final price. And because so many people buy generics, pharmacies and PBMs push for the lowest possible cost. Some generic drugs are sold below manufacturing cost just to keep shelves stocked. That’s why shortages happen-when prices drop too low, manufacturers quit, and then one company corners the market and raises prices again.Why Europe Pays More for the Same Pills

In Europe, the government steps in. Countries like Germany, France, and the UK don’t let the market decide. Instead, they use centralized price negotiations. A government agency looks at how much a drug costs in other countries, what it’s worth medically, and what the national budget can handle. Then they set a price-and manufacturers either accept it or don’t sell there. This system works great for keeping overall drug spending low. In 2023, the average European country spent $621 per person on pharmaceuticals. The U.S. spent $1,443. But here’s the catch: those low prices come at a cost. Because there’s less competition, generic manufacturers don’t have the same pressure to slash prices. Only 41% of prescriptions in Europe are for unbranded generics, compared to 90% in the U.S. Fewer players mean less downward pressure on prices. And it’s not just about volume. European countries often require doctors to approve switching from a brand to a generic. In Germany, pharmacists can substitute generics automatically. In France, they can’t. That small difference affects how fast generics take over-and how much competition exists.

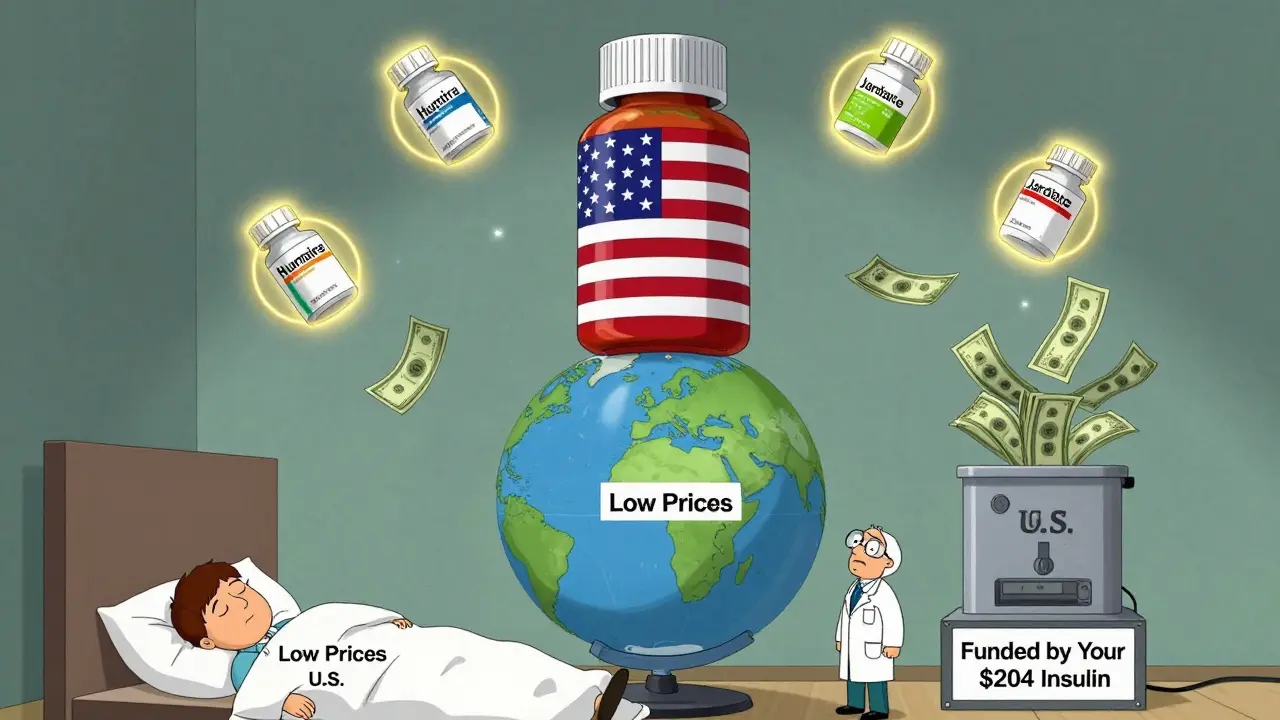

The Brand-Name Paradox: Who’s Subsidizing Whom?

Here’s the real story: Americans pay far more for brand-name drugs than anyone else. In fact, U.S. prices for those drugs are over four times higher than in most OECD countries. That’s not because Americans are greedy. It’s because the U.S. market is the main engine funding global drug innovation. According to the IQVIA Institute, the U.S. accounts for 40% of global pharmaceutical sales, even though it has only 4% of the world’s population. That means the profits from U.S. brand-name sales help pay for research on new cancer drugs, diabetes treatments, and Alzheimer’s therapies that eventually reach patients everywhere. Experts like Dana Goldman from the University of Southern California say Europe is effectively “free-riding” on American innovation. European governments negotiate prices so low that manufacturers couldn’t recover their R&D costs without the higher U.S. prices. The numbers back this up. Between 2015 and 2023, 55% of all new drug approvals were first launched in the U.S. That’s because companies know they can recoup their investment here. When Medicare started negotiating prices for 10 drugs under the Inflation Reduction Act, the negotiated prices were still 1.6 to 3.9 times higher than in other countries. Jardiance cost Medicare $204-still nearly four times what it costs in the UK.What Happens When the U.S. Tries to Cut Brand-Name Prices?

The Inflation Reduction Act is the biggest change to U.S. drug pricing in decades. Medicare can now negotiate prices for a small list of expensive brand-name drugs. But here’s what experts warn: if the U.S. forces prices down too far, manufacturers will raise prices elsewhere to make up the difference. Alexander Natz of the European Confederation of Pharmaceutical Entrepreneurs warned in October 2025 that if the U.S. adopts a “most favored nation” policy-where it pays the lowest price any country pays-it could slash U.S. drug profits by $100 billion a year. That would force companies to increase prices in Europe, Japan, and Canada to keep funding research. In other words, cutting U.S. brand-name prices might not help global affordability-it could hurt it. The same risk exists with price controls. When the UK’s NICE says a drug isn’t cost-effective, it doesn’t get covered. Patients wait. Or they pay out of pocket. In the U.S., even if a drug is expensive, it’s usually covered-because the system absorbs the cost through insurance and rebates. Europe’s system is more transparent, but it’s also more restrictive.

Real People, Real Prices: What Patients Experience

Ask an American with Medicare Part D: they’ll tell you their monthly generic co-pay is $0 to $10. Ask a German patient: they’ll pay a fixed co-pay of €5 to €10 per prescription-no matter if it’s a generic or a brand-name drug. So even if the actual drug cost is lower in the U.S., the out-of-pocket experience can feel similar. Reddit threads from early 2025 are full of Americans who’ve traveled to Europe and been shocked by the price of generic pills. One user wrote: “I paid €15 for a month’s supply of lisinopril in Berlin. Back home, my pharmacy gives it to me for $4.” Meanwhile, Europeans who’ve visited the U.S. are stunned by the cost of insulin or Humira-drugs that cost hundreds or thousands of dollars here, but under €100 in their home countries. Pharmacists in the U.S. report something else: the race to the bottom. Some generic drugs are so cheap that companies stop making them. In 2024, there were over 100 drug shortages in the U.S., many tied to generics. When one manufacturer leaves, prices can spike overnight. It’s a fragile system.The Future: Will the Gap Close?

The U.S. generic market isn’t going away. It’s too efficient. Too many people rely on it. Even if Medicare negotiations bring down brand-name prices, the system for generics will stay the same: competition, volume, and low margins. Europe may eventually loosen its price controls to keep access to new drugs. The European Medicines Agency admitted in 2025 that current pricing policies could limit patient access to innovative therapies. Meanwhile, the U.S. is under pressure to stop being the world’s drug subsidy. But if it cuts brand-name prices too fast, it risks slowing innovation globally. The truth? The U.S. doesn’t have the cheapest drug prices overall. It has the cheapest generic prices-and the most expensive brand-name prices. That’s not an accident. It’s the cost of funding the future of medicine.For now, Americans get the best deal on generics. But that deal depends on the rest of the world paying more for the drugs that haven’t gone generic yet. Change one side, and the whole system shifts.

Bro, this is wild. US generics are basically a public utility at this point. Teva and Sandoz are running on razor-thin margins, sometimes selling below cost just to stay in the game. It’s not charity-it’s volume economics. Meanwhile, Europe’s price caps kill competition. No one’s gonna invest in making lisinopril if they can’t undercut the guy next door. We’re the global R&D engine because we let the market scream. Europe gets the benefits without the pain. It’s not unfair-it’s just capitalism with a side of free-riding.

As someone who’s filled prescriptions in both rural Georgia and rural India, I’ve seen the invisible architecture behind these prices. The U.S. system isn’t perfect-it’s chaotic, fragmented, and sometimes cruel-but the sheer density of generic manufacturers creates a natural downward spiral that no regulator could engineer. Europeans pay more for generics not because they’re ‘better’ at healthcare, but because they’ve chosen stability over competition. And honestly? That’s a luxury many can’t afford.

This article is a load of corporate propaganda dressed up as economics. The U.S. doesn’t ‘fund innovation’-it’s a monopoly racket. Pharma lobbyists wrote the laws. PBMs pocket rebates. Insurers pass the cost to patients. And now you’re telling me that Americans paying $1,000 for insulin is ‘necessary’? That’s not capitalism-that’s extortion with a PhD. Europe’s system is transparent. Ours is a rigged casino. And you’re defending the house?

Y’all need to chill. I paid $3 for metformin at Walmart last week. My cousin in London paid €12 for the same thing. Who’s the real villain here? The guy who makes the drug? Or the government that says ‘nope, you can’t charge more than €10’? The U.S. system is messy, but it works. We get new drugs faster. Europe gets old ones slower. And guess what? I’d rather have a shot at a cure than a fixed €5 co-pay that locks me out of the future.

From India, I’ve seen how generics are made-small factories, low wages, high volume. The U.S. system lets these manufacturers survive because the market is huge. In India, we pay pennies too, but because of scale and labor, not because of competition. The U.S. is the only place where a $4 pill can be made, sold, and delivered profitably. That’s not magic-it’s math. And honestly? I’m glad it works. More people get medicine. That’s the real win.

Let’s be real. The ‘U.S. funds global innovation’ narrative is a distraction. Big Pharma spends more on marketing and stock buybacks than R&D. The real innovation comes from NIH-funded research-paid for by U.S. taxpayers. So we’re not ‘subsidizing’ the world-we’re being robbed by corporations who take public money, patent it, then charge the world double. Europe isn’t free-riding. They’re just not letting the wolves in the boardroom eat their citizens.

I’ve had diabetes for 15 years. I pay $12 a month for insulin here. My sister in Canada pays $5. My friend in Germany pays €3. And yeah, I know the ‘innovation’ excuse. But when your life depends on it, it’s not about innovation-it’s about dignity. The U.S. system isn’t efficient. It’s cruel. And pretending that $4 generics justify $700 insulin is moral bankruptcy wrapped in economic jargon.

Oh, so the American patient is the noble martyr, subsidizing the ‘ungrateful’ Europeans with their suffering? How poetic. The real tragedy isn’t that Europe pays less-it’s that Americans have internalized exploitation as patriotism. We don’t fund innovation-we fund shareholder dividends. And the fact that you call this ‘capitalism’ is proof that the word has been hollowed out by corporate PR. Next you’ll say the Titanic’s lifeboats were ‘efficiently allocated.’

Let’s unpack the PBM layer. PBMs don’t negotiate for patients-they negotiate for profit. The rebate system incentivizes higher list prices. So even if your generic is $4, the list price is $20, and the PBM takes $16. That’s why drug prices are opaque. The $4 you pay? It’s a decoy. The real cost is buried in premiums and deductibles. Europe’s system isn’t perfect, but at least you know what you’re paying. Here? You’re paying for a fantasy.

US generics are a race to the bottom. Shortages. Zero profit. No innovation. Europe’s system is slow, sure-but it’s stable. And guess what? No one’s dying because they can’t afford lisinopril in Berlin. Meanwhile, in the US, people skip doses because the co-pay jumped to $15. This isn’t ‘efficiency’-it’s a Ponzi scheme where the patient is the last sucker.